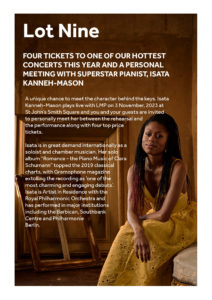

A chat with Isata Kanneh-Mason and Jonathan Bloxham

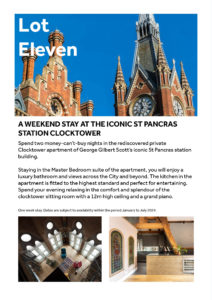

Beethoven and Mendelssohn with Isata Kanneh-Mason at St John’s Smith Square

Friday 3 November 2023

Isata Kanneh-Mason piano

Jonathan Bloxham conductor

Ruth Rogers leader

London Mozart Players (LMP)

Arvo Pärt Cantus in Memorium Benjamin Britten

Anna Clyne Stride

Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No.1

Beethoven Symphony No.5

Before our concert together at St John’s Smith Square, we sat down with our soloist Isata Kanneh-Mason and conductor Jonathan Bloxham to talk about the concert, the music, and pre-concert rituals…

Isata Kanneh-Mason

- Can you tell us about your favourite moment in the Mendelssohn Piano Concerto?

It’s the opening. It’s so dramatic and exciting and I like the way the piano states its presence. Actually I also have another moment in the second movement where the piano is playing slow chords and there is a solo cello line – the harmonies there are so incredibly beautiful. - We performed the Mendelssohn two years ago with you at Cadogan Hall. How does it feel to be playing this piece together again?

It’s really lovely to perform this piece with the same group of people. I feel I have developed as a musician over the last two years so it will be nice to be able to bring something different to the performance. - Do you have a pre-concert ritual, and if so, what is it?

I try not to stick to a specific pre-concert ritual in case I don’t have time. I always make sure I stretch, warm up my fingers and drink water. I don’t tend to eat too much before going on stage as I don’t want to feel full. And I also put away my phone quite a while before a performance as well, so there are no distractions!

Jonathan Bloxham

- In your role as Conductor in Residence and Artistic Advisor of LMP, you developed the programme for this concert. Can you explain how you chose the pieces and put them together?

Programming is one of the great joys of my work as a conductor, and devising each programme comes with its own intellectual or emotional journey. The inspiration for this concert began with Mendelssohn. Not only a prodigious composer, he was also a virtuosic pianist, and as a young boy he discovered and formed a deep appreciation of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. From then on Beethoven’s music had a huge influence on his own compositions, and Mendelssohn continued to perform the master’s works throughout his life. In 1847, the year of his death, he took his final visit to Britain and performed Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4. This ties in themes of London, Mendelssohn, the piano and Beethoven. Taking the second two of these we arrive at Anna Clyne’s wonderful piece – Stride – a piece for strings based on the themes from Beethoven’s Pathetique Sonata. And finally, our opening piece, Pärt’s Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten is not only one of the most atmospheric openings of a concert, but it is also a little nod to the 110th Anniversary of Britten’s birth. This is a programme I adore.

- Beethoven’s Symphony No.5 is such an iconic work. How do you take on the challenge of conducting it?

It is of course an iconic work to play as well as conduct! Even just the opening is an infamously treacherous moment for us all. But what an honour it is to have the chance to perform this majestic piece with LMP. For me personally, it was in the second half of the very first symphonic concert I conducted as a student and so brings back many memories. This piece has taught me a great deal about the craft of conducting.

- You’re also conducting Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto, which will be played by Isata Kanneh-Mason. What’s the relationship like between the conductor, soloist and orchestra when performing this piece?

Every player in the LMP is a fantastic chamber musician. And every time they perform, be it with or without a conductor, they are making chamber music. And so it is no different when a soloist joins. As a conductor in this scenario I feel my role is to help focus all our listening, to facilitate the connection between soloist and orchestra and to be a conduit for the flow of ideas between them…and adding a few of my own now and then too!

LMP, conducted by Jonathan Bloxham, play Beethoven and Mendelssohn with Isata Kanneh-Mason on 3 November 2023. Tickets can be purchased here.